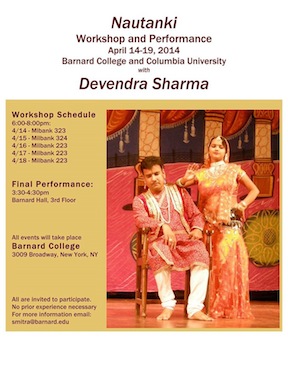

A Brief History of the Nautanki Performance Tradition

Nautanki actress Sitara in Nautanki "Amar Singh Rathore"

Photo credit: Devendra Sharma

The history of the Swang-Nautanki1 performative tradition goes back several hundred years. In recorded form, we find references of Nautanki in a 16th century book called Ain-e-Akbari written by Abul Fazal, a scholar at the court of Emperor Akbar in India (Agrawal, 1976). Nautanki's origins lie in the folk performance traditions of Bhagat and Raasleela of Mathura and Vrindavan2 in Uttar Pradesh3, and Khayal of Rajasthan4 (Agrawal, 1976). Nautanki's history becomes clearer in the nineteenth century with the coming of the printing press in India and publication of Nautanki operas in the form of chap-books (Hansen, 1992).

In the late nineteenth century, Hathras and Mathura2 in western Uttar Pradesh, and Kanpur and Lucknow2 in central Uttar Pradesh, became the two biggest centers of Nautanki performance and teaching. The Hathras School developed first, and performances by its artists in central Uttar Pradesh stimulated the development of the Kanpur-Lucknow School of Nautanki. Both schools differ from each other with respect to their performative form and technique. While the Hathrasi (literally meaning 'of Hathras') School emphasizes singing more and is operatic in form, the Kanpuri School centers itself more on prose-filled dialogues mixed with singing. This style developed during colonial times (19th and early 20th centuries), when India was under British rule. The Kanpuri style borrowed many elements of prose dialogue delivery from Parsi Theater (a theater genre inspired by European theater traditions), and mixed them with the Hathrasi singing to come up with its new style of performance. Also, the singing style in the Kanpuri School is somewhat fast-paced compared to the Hathrasi School.

Nautanki reached the pinnacle of its glory in the early 20th century when numerous Nautanki performing troupes, known as mandalis (literally meaning 'groups') and akharas (literally meaning 'wrestling arenas') came into existence. Nautanki mandalis were called akharas due to the prevalence of the particular style of singing in Nautanki that required a lot of physical power. The Nautankis staged by these mandalis or akharas became the main source of entertainment in the small towns and villages of northern India, and remained as such until television and VCRs began to make inroads in the early 1990s.

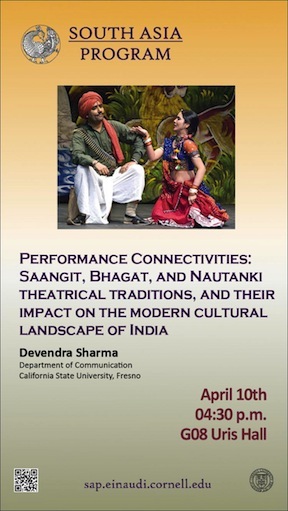

World-renowned folk artist Pandit Ram Dayal Sharma and comedian

Kishan Swaroop "Awara" in a Nautanki performance

Photo credit: Devendra Sharma

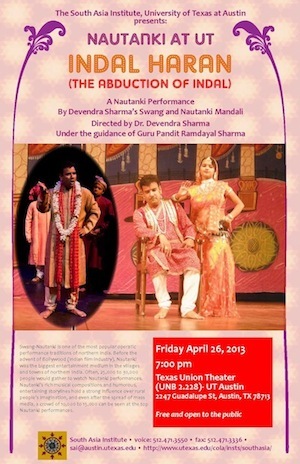

Riding on its popularity, Nautanki progressed both in terms of form as well as content, and its stage became bigger and more professional. Nautanki companies like Natharam's mandali, catching the cue from big Parsi theater (an urban Indian theater style) troupes such as Alfred Theater Company, started to present their performances outside the core region of their audience. Some performances occurred as far as Myanmar. Storylines of Nautanki ranged from mythology and folklore to tales of contemporary heroes. Thus, while Nautanki plays such as Satya-Harishchandra and Bhakt Moradhwaj were based on mythological themes, Indal Haran and Puranmal originated from folklores. In the first half of the 20th century, the contemporary sentiments against British rule and feudal landlords found expression in Nautankis such as Sultana Daku, Jalianwala Bagh, and Amar Singh Rathore.

The Nautanki tradition still has a strong hold over the imagination of people in rural north India. Even after the rapid expansion of mass media such as television and radio, a crowd of 10,000 to 15,000 people can easily gather at Nautanki performances. Like many other folk forms of India, Nautanki's status has been badly affected by the apathy of the political leadership, and the attitude of looking down upon indigenous Indian artistic traditions by powerful urban-based elites suffering from a post-colonial hangover5.

Nautanki: The Contemporary Scenario

At present, Nautanki is experiencing a dialectical tension. On one hand, it still holds an important place in people's collective imagination, and on the other, it is struggling to deal with changing audience aspirations, molded by cinema and television. On top of this, Nautanki has failed to contemporize the subject matter of its script (Sharma, 2004). One may ask the question: Why might a teenager in India watch a Nautanki depicting the 350-year-old heroics of the famous historical warrior Amar Singh Rathore? Times have changed and the context of these old Nautankis is perhaps not as relevant for today's audiences. During colonial times, these narratives had a specific function. Amar Singh Rathore, for instance, provided a catharsis to the subdued sensibilities of a colonized nation by giving them hope. People identified themselves with such heroes, and imagined themselves fighting against the colonial authority and oppressive elements through them (Hansen, 1992). After gaining independence, this colonial context is no longer valid. Audiences today want to watch Nautankis that mirror and discuss their own realities, rather than those which depict narratives from a remote past. People prefer to listen to stories woven around current issues that affect them; for instance, the ill-effects of outdated social traditions like dowry, side effects of agricultural pesticides, unemployment and poverty, and women's empowerment. In essence, they want to make sense of the world around them (Burke, 1969). A community performing art can help in this endeavor (Bakhtin, 1984). When a folk popular form stops fulfilling its function, it ceases to be a popular form. This is a real danger that Nautanki is facing in present-day India. So Nautanki has to keep up with the times.

It would be incorrect to put the full blame for not moving with the times on Nautanki, or for that matter on any other indigenous performance tradition. The failure of many of these traditions to keep up with the changing realities of society has been a result, in many ways, of developments in India's high brow (Bourdieu, 1984) culture, and attitudes of "the custodians of high art" towards the folk or ordinary culture (Williams, 1958). The development of arts and theater in colonial, and particularly in post-colonial India, has taken a path full of contradictions (Jain, 1967). On one hand, most people working in the field of performance in the post-Indian independence years looked up to Western models of theater for inspiration, or they at least sought the approval of the West for their efforts. Only a handful of folks chose indigenous performance forms to make contemporary statements. On the other hand, the upper and upper-middle classes adopted a kind of superficial missionary zeal toward saving the indigenous folk forms. They used folk culture to increase their cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984), a way to distinguish themselves from the so-called "ordinary" or common people. They looked at folk forms as artifacts frozen in time, which they could use to decorate their houses, like old paintings. Thus many times, the Indian elite, through government or private grants, attempted to preserve folk forms. They wanted the "pure" folk art form, unspoiled by any adulteration, to be used as an escape to a fantasy world away from their everyday realities. Folk forms functioned as a toy, an amusement, a showpiece for the high-brow elite. This situation continues.

What people from the so-called high-brow culture fail to fully realize is that folk or popular arts cannot be preserved. They are ever flowing, ever changing expressions of people, reflecting their contemporary realities. What can be done is to provide these folk forms with equal opportunities and a level playing field in relation to their urban counterparts, giving them opportunities to express contemporary realities. In post-colonial India, folk forms have either been seen as art forms incapable of intellectual expression, or they have been given a rare species status. In both scenarios, community folk forms like Nautanki have been neglected by those who control socio-economic and cultural capital. Unfortunately, Nautanki artists and others associated with these forms either do not have enough resources or educational capital to make a case for their art, or are so caught up in their struggle for survival that they have time for little else.

In sum, if Nautanki or other similar community folk art forms are to survive (if not thrive), they need opportunities to adapt in a changing context. They cannot survive by continuing to portray outdated themes. If they are given this opportunity, it can be a win-win situation. For instance, development agencies interested in communicating social change messages would get a possibly effective medium to reach rural audiences with contemporary themes.

Already some efforts have been made in this direction. Recently some performing troupes have used Nautanki to grasp and incorporate Indian society's contemporary concerns for social change and development (Brij Lok Madhuri, 2003). Brij Lok Madhuri (BLM) is one such troupe. BLM was founded by renowned Nautanki singer and actor Pandit Ram Dayal Sharma in the 1970s to promote the use of folk forms for purposive social change. As a community art form, Nautanki is a more "real" and live art form than television and video can ever be, and also closer to the culture of rural and semi-rural people. Working with the Government of India and Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (JHU/CCP) from 1999 to 2004, BLM created new scripts for Nautanki and other folk forms on pro-social messages such as small family size, women's empowerment, dowry eradication, and HIV-AIDS prevention. BLM trained over 150 folk troupes to perform these scripts in north Indian villages (SIFPSA, 2003). By 2003, over 10,000 performances had been given by these troupes in as many villages. This contemporary use is giving an edge to Nautanki.

Recently, Nautanki has been introduced in America by Dr. Devendra Sharma, a Nautanki artist, singer, writer, director, and scholar of communication and performance. The participants in Dr. Sharma's productions are engineers, doctors, and other members of the Indian diaspora living in America, who are given a rare opportunity to connect with their cultural roots. At the same time, these performances have exposed other communities in America to Indian culture. One such Nautanki is Mission Suhani, an original Nautanki co-authored by Dr. Devendra Sharma and Pandit Ram Dayal Sharma that communicates a contemporary and controversial social issue concerning Indians and Indian immigrants in America. This Nautanki critically examines the phenomenon of some Indian men who come to America to study or work, but go back to India and get married, either because of parental pressure or to get a big dowry (cash given to the groom's family by the bride's side). Many of these men leave their wives in India and never bring them to America, where they often have another wife or a girlfriend. One of the unique aspects of this Nautanki is that it is bilingual (both in Hindi and English). This protects the traditional operatic and artistic elements of Nautanki while also effectively communicating the story and contemporary social issue to a diverse audience. Contemporary Nautankis such as Mission Suhani involving global social issues help to update Nautanki to emerging issues in contemporary society in India and around the world.

- 1I refer to Swang-Nautanki as Nautanki for the sake of convenience

- 2Mathura, Vrindavan, Hathras, Kanpur, and Lucknow are all towns in Uttar Pradesh

- 3Uttar Pradesh is a state in north India

- 4Rajasthan is a state in north India

- 5Colonial after-effects on the psychology of Indian elites

References