From Mudhera Village to San Francisco, California

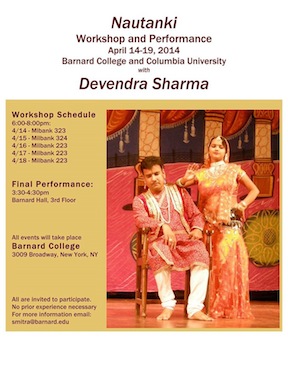

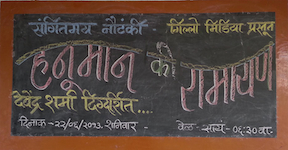

Devendra Sharma performing with his father, renowned

Nautanki artist Pandit Ram Dayal Sharma

Photo credit: Devendra Sharma

I was born in a small village called Samai-Khera in Bharatpur district of India's Rajasthan state some 25 years ago. Samai had around 500 families and a population of around 2,500 people. There was no electricity in the village, and we had to walk for five to six miles to reach the nearest bus station. Our house was made of mud and reed. I remember it was a beautiful house. My grand parents had never gone to school. They could not read or write; however they were wise. My grandmother was immensely talented. She had single-handedly carved solid mud pillars in front of our house, and painted its walls with various folk motifs. She used to draw and sing really well. When I was born, family's financial situation was pretty bad. The financial pressures were such that my father abandoned his studies when he was in high school and began working.

Rajasthan, the name of our state, literally means "the land of princes." Prior to gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1947, Rajasthan was composed of a number of principalities, each ruled by a prince. These principalities, although under British oversight and paid taxes to them, were fairly autonomous in their internal matters. Thus when I used to sleep on a charpai1 under an open sky in front of our mud house, my grandfather used to narrate stories of kings and princes to me. Staring at the Milky Way, I used to be transported to a different world.

My grandfather had been a famous wrestler of Bharatpur principality in his youth. I remember him as tall and fit. He had won many competitions and beaten many big wrestlers. He also told stories about his wrestling prowess. One of them is still carved on my mind. In his twenties, he went with a Barat2 to another village. During the wedding festivities, some people from the bride's village challenged my grandfather to fight a kushti (wrestling match) with a famous wrestler of their village. My grandfather agreed to fight, but on one condition. There was a person from our village in the Barat who was not very good looking and thus nobody was ready to marry him. My grandfather said that if he won the wrestling match, the villagers would have to marry one of their daughters to this person. The villagers agreed. The wrestling match took place and my grandfather won. The wedding party returned with not one but two brides. Even now, people in my village talk about this incident. Listening to this, I remember how proud I was of my grandfather. However, I was also curious about the fate of the girl who was married to the "not so good looking guy" as a result of this wrestling match. My grandfather told me that the wedding worked out fine and the couple lived a happy married life!

There were other kinds of stories that I loved to hear from my grandfather. These stories were about Nautanki. Nautanki is folk musical theater form and until a few decades back, was the most popular form of entertainment in rural north India—even more popular than cinema. I remember Nautankis as performances that lasted for a whole night, and every body, including us kids, just loved them. Apart from being a wrestler, my grandfather was a famous artist in a Nautanki troupe. His younger brother also worked with him. My grandfather told us stories of audiences treating him and his brother as "divine" beings because they used to sing so well. In particular, I loved his story about the incident when he confiscated the Harmonium (a musical instrument used in Nautanki) of his troupe because the dishonest troupe owner did not pay a salary to his brother. Without the harmonium, performances could not happen. He told me that he had no other choice but to confiscate the harmonium because he and his brother did not even have money to buy food. He only returned the harmonium when they got their money. Of course, nobody could challenge my grandfather because he was a wrestler!

My grandfather used to tell me that my father grew up to become one of the biggest stars of Nautanki. So big that everybody in surrounding districts knew him by his name. He told me how proud he was of his son, i.e., my father, when he saw people in thousands thronging to see his performances. Slowly as my father became a nationally famous performer, our financial situation improved. My grandfather told me how for the first time in history, the name of our village was broadcast from B.B.C. London when my father was visiting England for a performance and B.B.C. aired his interview. Every person in our village felt so proud; their own boy was speaking from London, and Angrez (British) were giving so much respect to him! Through these stories of my grandfather, my father became my biggest hero. I dreamed of becoming a great singer like my father, to be worshipped by audiences like he was, to be on the top of that stage called Nautanki.

Another memory, belonging to a much later time, comes to mind when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Delhi. My siblings and I were now living in Delhi, the capital of India, with our parents. My grandparents still lived in my village with my uncle's family. I was traveling to meet them during my summer vacation. When I reached, by bus, the small town of Goverdhan six miles from our village, it was dark. There were no buses running to my village. The only improvement from my childhood days was that instead of walking all the six miles, we could take a tonga (a horse carriage) for three miles and then walk the remaining three miles on foot. I inquired when the next tonga was going to my village. I was informed that the last tonga had already left. The only way to reach my village was to walk the six miles in pitch darkness through agricultural fields and a forest. People at the tonga stand told me that it was not safe to travel on foot after dark. I did not know what to do. There were no hotels in this small town and I did not know anyone there with whom I could stay for the night. Suddenly I heard a voice, "Which village do you want to go?" I turned around to find a person in his forties, sitting on the driving seat of a big farm tractor. Although small, Goverdhan is the only town in the vicinity of many villages, and therefore many farmers come to Goverdhan to sell their produce and to buy supplies. There were many tractors parked near the tonga stand. There were also a few workshops where some tractors were being serviced. The person who asked me the question had already started his tractor and was ready to go. He must have heard my conversation with the tonga people. My conversation with him continued in the following manner:

I: I have to go to Samai-Khera.

Person: Oh, Samai-Khera. I am going to Petha, in the opposite direction, or I could have dropped you. I am sorry.

I: That's all right.

Person (moves his tractor ahead, but then stops): Well you are from Samai-Khera. Do you know the famous Nautanki actor Master Ramdayal? He is very good looking and very young. I saw him in a performance in my village long time back. I know that he is from Samai-Khera.

I: Yes I know him very well.

Person (gets down from his tractor): Oh, you know him! Please tell me more about him. How is he? Where is he? We have not seen his performance for a long time now. Our whole village wants him to perform again in our village.

I: Well, he is my father.

Person: He is your father? You are kidding! He is so young. How can he have a son so old? Besides he is so good looking.

I (a bit annoyed): When did you see his performance last?

Person: Around 20 years ago.

I: So you think he would remain the same young boy even after so many years?

The person felt a little embarrassed. During this time, a small crowd had gathered around us. Knowing that I am the son of the famous Nautanki star Master Ram Dayal Sharma, the tractor driver and many other people began asking questions about my father. I felt overwhelmed by the fandom of my father. The tractor driver requested me to accept his hospitality for the night. This, he said, would give him an opportunity to do some service to his favorite singer's son. I thanked him and informed him that I had to urgently reach my village that night. The person then gladly dropped me to my village, driving on a dirt road through a forest. I was amazed by the popularity of a Nautanki star. The tractor driver informed me on the way that Nautanki has been the most popular source of entertainment not only for his village community, but for the people in the region. Nautanki stars are "gods" for them. I wondered what was in this art form that makes people identify so much with it.

I was eight years old when I had my first Nautanki experience. That night, I was attending my father's cousin's wedding in Mudhera, a small village in Bharatpur district. I had come to attend the wedding with my grandmother and my paternal uncle. While playing with the other kids, I overheard that a Nautanki troupe had been invited to perform that night, and my father was going to make an appearance as the star performer. I got very excited and decided to keep awake until the Nautanki started. Although I had heard that my father was a big Nautanki performer, I had never seen him perform on a Nautanki stage in a village. We were living in Delhi at that time. So I kept myself awake that night with great difficulty. I saw that thousands of people were gathering in the vast open grounds in front of my grandmother's paternal home. Many of them, I learned, were coming form adjoining villages. They were coming on foot and in bullock carts with sturdy bamboo sticks in their hands. A platform made up of wooden cots was being assembled in middle of the ground. We used these cots to sleep on. I asked my uncle why they were being assembled. He informed me that the stage for Nautanki performance was being constructed with the cots. I saw that a tight rope was connected from one end of the platform to another and many gas-filled lanterns were hung on it for illumination. I remember the wonderment these bright lights held for us, as our village homes only had dim lanterns. There was much excitement in the air.

People were milling around. They were taking their seats on the bare ground and getting ready for the performance. I was immensely curious. I remember seeing a huge crowd behind the stage. I tried to make my way through the grownups but could not. However, I saw a glimpse of some people putting on glittering costumes. I guessed they were performers. I could not find my father there. It was very noisy. I heard many people inquiring about my father. They were shouting that they will not let the performance happen if Master Ram Dayal had not arrived from Delhi. I was praying that my father would be there. I did not want to miss this opportunity to see him perform the main role in a Nautanki.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the audience. I heard people shouting that Master Ram Dayal ji had come. People were running back to take their place. I was thrilled. I tried to go back stage to reach my father. However there were so many people there, each pushing the other to see my father, that I could not reach him. I heard some one calling my name from behind. It was my uncle. He made his way through the crowds and took me to my father, who, meanwhile, was changing his dress behind the stage. There were hundreds of people watching him. Seeing me, my father hugged me as he always did. I was so happy. I could not believe that I was the son of this big star. Was I? I looked around and found people looking at me with admiration. I was proud. My father arranged for me and my uncle to sit on the stage itself. There was 10 years of difference between me and my uncle and we were like friends. We both established ourselves firmly near the accompanying instrumentalists on one side of the stage. The harmonium player had started to play Nagma3 already and the Nakkara4 player was providing accompaniment. The sharp and loud sound of Nakkara was reverberating in the whole village. It could be heard over miles. Sitting on the stage I saw people still making their way to the performance grounds on foot, bullock carts, and tractors. Many bullock carts and tractors were parked in between the audiences. People were sitting on ground, on their bullocks-carts, on tractors, on roofs of houses, on walls, on platforms in front of their houses, and some were even hanging from trees. They were talking to each other, laughing, sharing jokes, smoking, eating, drinking chai (tea), and doing other activities. I was really liking the warm-up tune that was being played on harmonium and Nakkara, and waiting eagerly for the performance to start. Hundreds of people would occasionally shout a jaikara (a slogan spoken in a chorus) of Giriraj ji or Krishna ji (our local deity) --"Bol Giriraj Maharaj ki Jai" (Praise Giriraj!). The atmosphere was electrifying!

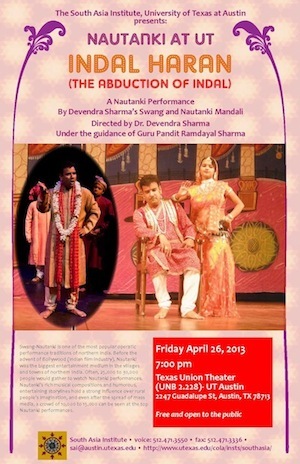

Finally the Nautanki started at around 11 pm. I was mesmerized as soon as it started. I am having difficulty in describing it. I had not heard such melodious and powerful singing before that night and never did after that. Over the years, I have heard thousands of film songs, classical and light compositions on radio, television, and live concerts but they pale in comparison to the wonderful opera that I heard that night in Mudhera. As the night passed, the performance got even better. At one time, people were so absorbed in the performance that there was a pin drop silence. Imagine that in a crowd of thousands of people! My father's performance, as I remember it, was ecstatic. Many times during the performance, I had goose pimples. It was so good! The Nautanki "Indal Haran" was performed that night. The audience participated in the performance in many ways. For instance, some audience members were giving spontaneous cash awards to performers after well sung pieces. A person, on stage, was specially designated to make a list of rewards and collect money from the reward givers. After he collected enough rewards, say 10 or 15, he would signal performers to take a short break, and then announce the names of the reward givers, names of the performers to whom the rewards were given, and the amount of the reward. There were endless rewards given to my father. As his son, I, with my uncle was given the responsibility of keeping the money that was awarded to my father. I remember I felt very important. Soon there was a mountain of currency bills in front of me. My uncle and I were both counting the bills and also watching the performance. I was excited and trying to guess how much reward money would come in by the morning.

I remember at one point in the performance, two audiennce members competed in giving reward money to my father. One of them, my uncle told me, was the superintendent of the local police, and the other was a local landlord. The competition started with cash rewards. One of them would announce a certain sum of money to be given to my father as a reward for a piece sung by him. Then the other person would increase the amount of money after my father's next piece. The audience was not only enjoying the performance but also this reward-giving competition. After every announcement, thousands of people would hail the person giving the reward. Soon the amount reached in thousands of rupees. They did not stop there. One of them announced that he was giving my father a few acres of his land as a reward for his wonderful singing. Finally my father had to stop singing. He requested those two audience members to not indulge in unhealthy competition and returned all the rewards given by those gentlemen. By now, I had forgotten about my sleep totally. I was enjoying the performance and counting the currency bills!

The performance finished when the sun rose. The story of Indal Haran concluded. However, the people were not ready to budge. They requested one song after another from my father. My father obliged them as far as he could. Then he requested the audience to let the performers get some rest after singing the whole night. He also reminded audiences that they also had to get back to their villages and get on with their work. I noticed that my father had a tremendous clout over the audience. Whatever he requested, they accepted. Reluctantly the audience agreed to my father's advice but demanded a final romantic number from him and the heroine of the Nautanki, a famous female artist named Prem Lata. After that song, the performance finally ended.

Surprisingly, even after being awake the whole night, I was not feeling tired. I wanted the performance to go on like other audience members. After the performance ended, I ran to my father, and he hugged me. My uncle showed my father the large amount of money that had come as rewards. My father distributed that money on the spot to his junior artists and instrumentalists. Later he explained the reason for this. He told me that the big artists usually get all the rewards and money and the small artists and instrumentalists get little. I felt so proud of my father that day--not only because he was a great performer but because he was also a caring human being. Now, more than ever, I wanted to be a big Nautanki artist like him.

I have never quite been able to recover from that heady experience in Mudhera. There was something in that Nautanki performance that I have never found in any other medium of entertainment. Since that performance, I have performed live in hundreds of shows in cities, I have seen and heard the most acclaimed television and radio programs, and films. I have performed in all parts of India, in Europe, and in America. However, even after all this, I never was able to get the immensely satisfying and fulfilling experience that I got watching Nautanki. Was it the presence of thousands of men and women, bullock carts, people on their roofs, melodious singing and acting, and reward-giving that made it such a memorable experience? I don't know. What was it that hooked me to Nautanki forever after that experience? I have not been able to put my finger on what exactly had appealed to me in Mudhera as an audience member. And perhaps it is not only me. I have talked to hundreds of fans of Nautanki and they all talk about the mesmerizing appeal of Nautanki. As I grew up, I decided that I would find out why Nautanki is so appealing to its audiences, and what made for that exciting community ambience during my first Nautanki experience in Mudhera.

- 1A cot made of bamboo or other kinds of wood

- 2The groom's wedding party that goes to the bride house during a wedding in India

- 3The melodious compositions played on harmonium to set the audiences' mood for the Nautanki performance

- 4A percussion instrument composed of two drums played by two wooden sticks. This instrument is unique to Nautanki. It is so loud that it can be heard over many miles. It serves to "advertise" Nautanki.